PARIS — André Courrèges, the father of Space Age fashion, and one of the earliest advocate of pants for women for dressed-up occasions, has died at the age of 92 after a 30-year battle with Parkinson’s disease, the house said on Friday.

Courrèges created a style that has at times been referenced by everyone from Marc Jacobs to Karl Lagerfeld and, at its height, was one of the key couturiers for the jet set. A 1965 WWD article was headlined in bold capital letters: “To wear Courrèges you must give yourself to him completely. Surrender.”

Rose and Jacqueline Kennedy, Gloria Guinness, Paulette Goddard, Françoise Hardy, the Duchess of Windsor and Lee Radziwill were among those who wore his designs.

With a desire to create clothing that was functional and liberating, Courrèges was one of the first designers to recognize the importance of ready-to-wear. “You don’t walk through life anymore. You run. You dance. You drive a car. You take a plane, not a train. Clothes must be able to move too,” he said.

This freedom of movement fueled his inspiration. “I feel there is a very strong mood in the air,” he said. “Women want to wear casual, sporty clothes by day.”

French Culture Minister Fleur Pellerin lauded Courrèges as an innovator in tune with the underlying shifts in French society during the Sixties.

“In the end, he invented a universe full of shapes and colors in which elegance could not be conceived without imagination, humor and a great freedom of expression and movement. Courrèges made the women he dressed happy,” she said in a statement.

Former Young & Rubicam ad executives Jacques Bungert and Frédéric Torloting, who bought the label from Courrèges and his wife Coqueline in 2011, paid homage to his drive to innovate.

“His whole life, André Courrèges, together with Coqueline, never stopped moving forward and inventing things to be ahead of the curve — a visionary designer who foresaw the 21st century and believed in progress. That is what makes Courrèges so modern today,” they said jointly.

Born March 9, 1923, in Pau in the Basque region of France, Courrèges originally trained as a civil engineer. He spent a short time working at the fashion house Jeanne Lafaurie, then became an assistant to Cristóbal Balenciaga.

He spent 10 years in the older designer’s atelier before founding his own house in 1961, a background reflected in his ingenious cuts and shapes, which, like those of his mentor, were inspired by geometry, in André’s case, by squares, triangles and trapezoids.

Courrèges was also very interested in modern architecture and technology, particularly that involving fabrics, and was one of the first designers to use plastic and PVC in his collections.

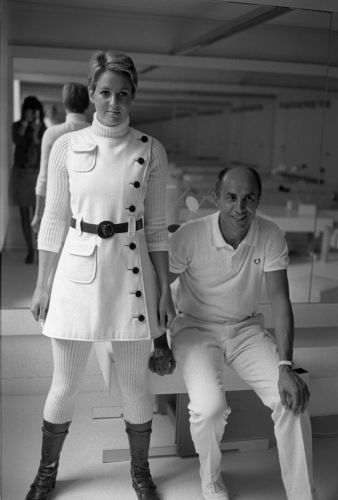

His 1964 spring collection radically redefined fashion with looks that were futuristic at the time, including dresses with cutouts; short, A-line skirts; poor-boy sweaters; slim pants, and goggles and helmets inspired by astronauts. Modified cowboy hats detailed with piping were another signature item.

Their color scheme was also futuristic: Clinical white laced with silver, primary colors and fluorescent tones. His sweaters and flat white boots, called “go-go boots,” were particularly influential among the general public.

The look was driven by Courrèges’ passion for the female body and the way in which it moved. “Look how we have failed,” he said in 1963. “A woman to drive her car must pull up her skirt. We have failed her in designing her clothes. There are occasions when pants are the thing to wear. They are more elegant on those occasions than any dress.”

His fellow futuristic visionaries included Paco Rabanne, Rudi Gernreich and Pierre Cardin.

Though of a totally different school, Hubert de Givenchy nostalgically recalled joining Courrèges and Balenciaga for nights at the opera or ballet as a young man. “It makes me sad. He battled a long illness,” he said, recalling the reaction when Courrèges launched his house in 1961.

“It had a resounding response. It was a young and different fashion — it was revolutionary,” de Givenchy said.

Courrèges continues to inspire emerging designers such as Simon Porte Jacquemus, who has a collection of Courrèges dresses from the Sixties.

“He’s one of the fashion figures who have inspired me the most, alongside Rei Kawakubo and Pierre Cardin,” said Jacquemus, lauding “his silhouettes, his obsession with circles, but most importantly his playful way of looking at things — fashion with a smile.”

Courrèges did not move with the times, but instead staked his highly specific claim to the futuristic and continued to sound what was once an ultramodern note — albeit one associated strongly with the Sixties — throughout his career.

His greatest muse was undoubtedly Coqueline. “I could not have perceived femininity without her,” he said. With her waiflike figure and precocious spirit, she modeled his designs to perfection and took a great deal of control over the house’s creative direction in the Eighties.

Courrèges himself was rarely seen without the same pink or white cropped pants, cropped hair, cropped jacket and a pair of pop glasses. He also retained the slenderness that had been a trademark throughout his life, which he attributed to an exercise regime that included working out, skiing and horseback riding.

Despite their growing fame, the couple preferred not to live an extravagant life. They took family vacations by trailer across the western U.S. and lived in an all-white apartment in the wealthy but quiet Parisian suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine.

The designer often said he felt more American than French. “I love America, I love the American spirit. The spirit of going to the moon. The American way of life. The grandeur of American space. America is a formidable, formidable country,” he said.

After retiring as his illness took hold, Courrèges devoted his time to painting and sculpture. His wife said in 2001, “He’s like a peasant farmer. He wakes up with the rooster, at the crack of dawn, and goes to sleep with the rooster, as soon as the sun sets.”

When the fashion tide turned against him, Courrèges channeled his energies into architectural and environmental design. He undertook projects such as the design of a Hitachi pavilion for a 1985 world exhibition and re-envisioned the company’s robots to give them a more human, poetic image. He teamed up with Minolta to design cameras so visually compelling women bought them for the packaging alone.

His innovations weren’t limited to the visual world. The couturier was also one of the first designers to enter into licensing. In the Sixties, he sold 50 percent of his business to L’Oréal, his fragrance licensee, and that arrangement lasted until 1983, when the Japanese company Itokin acquired the L’Oréal stake.

At the same time, Courrèges was expanding further into the American market with the help of Descente, a second Japanese licensee, and the Courrèges sportswear line Courrèges Sport Futur.

After buying the company in 2011, Bungert and Torloting set about relaunching the brand through collaborations with companies including Estée Lauder, Eastpak, Evian, Alain Mikli and La Redoute.

In September 2015, Courrèges staged its first catwalk show in 13 years, marking the critically acclaimed debut of Sébastien Meyer and Arnaud Vaillant as artistic directors of women’s wear.

Artémis SA, French billionaire François Pinault’s family holding company, is said to have taken a minority stake in the label as it prepares to expand its retail network, though officials at Artémis and Courrèges have declined to comment.

The designer is survived by Coqueline and his daughter, Marie.

SPACE AGE COUTURIER ANDRÉ COURRÈGES DIES AT 92

SPACE AGE COUTURIER ANDRÉ COURRÈGES DIES AT 92

SPACE AGE COUTURIER ANDRÉ COURRÈGES DIES AT 92