Warhol and Lichtenstein’s contemporary never saw himself as a pop artist, nor the nudes he painted alongside Coke bottles and bread as mere sex objects, insist his wife, daughter and former model as they meet at his old New York studio

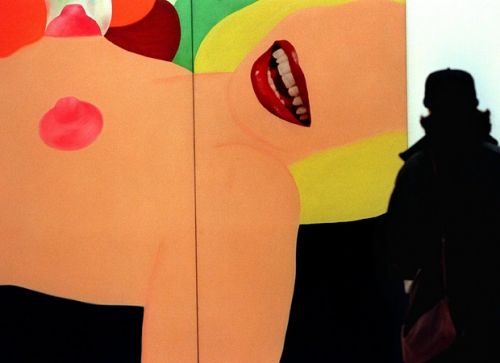

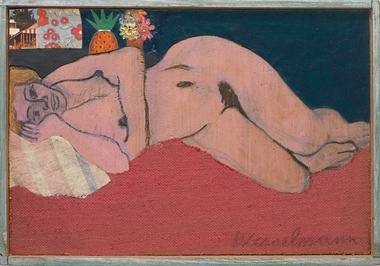

Sex is the thing that made the late Tom Wesselmann great, sometimes hated, and an oddity among his pop art peers. Unlike Warhol, Lichtenstein, Oldenburg and co, the painter chose the nude as his enduring subject, charging his work with a sexuality as earnest and joyful as it is overt.

The “pop artist” designation always rankled him, perhaps because his interest in the mass-produced images of contemporary American life was purely visual, rather than ironic. He intended no critique of consumerism, just a celebration of colour and shape. As his youngest daughter Kate Wesselmann says: “He was always going for form, composition, really strong imagery – whatever was going to make the most impact.”

We’re in the artist’s enormous ground floor studio in Manhattan’s Cooper Square, where the Wesselmann women – Kate, his wife Claire, and former model and assistant Monica Serra – have gathered. Wesselmann died in 2004, but his studio is still full of his life force. On the wall behind me is 2003’s sunny, winkingly reverent, Sunset Nude With Matisse Odalisque, in which a smiling but otherwise featureless blonde apes the pose of the Matisse painting behind her.

Serra, a petite and strikingly attractive woman who’s recognisable in much of his work by the visual shorthand of a black fringed bob and red lips, is recalling Wesselmann’s sweetness and humour when she suddenly points to the work. “That girl back there with her hands up and the Matisse behind her – for him that would be funny. It is funny! ‘Ironic’: maybe not.”

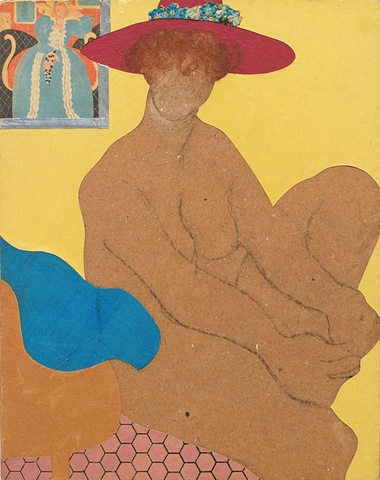

She and Wesselmann met in the 1980s when she was in her 20s and New York City was “really kind of a cool time”. Wesselmann was already a major name when a friend introduced her at one of his openings Soon after he asked if she might consider sitting for him. Early on in their friendship Wesselmann showed her some works that, as she puts it, “blew my mind” – a series of small-scale collages of interiors and nudes made with scavenged postcards and other bits of street ephemera. (Claire recalls having to carefully empty his jeans pockets of these precious scraps before she did laundry.)

These rarely seen early works now form a major show at London’s David Zwirner gallery. They presage the Great American Nude series, the work that would make Wesselmann’s name and years later, he said of these hand-worn prototypes: “They are so charming and cosy that it barely occurred to me anyone would find them alarming.”

Serra has a vivid memory of seeing them for the first time. “He went back into his closet and showed me these little collages and I was like, wait, this is you? Well, who is this artist?”

Those large-scale, flat and frictionless renderings of red-nippled nudes bothered plenty of people. Maybe it was the juxtaposition of still-life objects with female bodies that led some to accuse Wesselmann of equating one with the other – that women, in other words, were there to be consumed like the sliced white bread or Coke bottles that flanked them. The critic David Cohen sees it quite differently: “It is not […] that he was revealing the eroticism of a Coke bottle so much as the fizzy delight of a nude.”

When I ask Serra if she thinks his work has been misunderstood her eyes flash wide and she exhales a heavy: “Yes. I think it will be nice for people to see the sweetness of him. His sweetness and his precision and a depth that I don’t know if we always get. It touched me to see them, and still does.”

Wesselmann had, she says, “a fascination with women in a way I’ve never seen in a guy before… The reverence was so big. Almost like they had a magic, you know? I was just very earthy but he thought of me as ethereal – something special. He appears to be some to be some sort of misogynist or womaniser, when the opposite is true.”

From 1963 until his death, Wesselmann was married to Claire Selley, whom he met at Cooper Union where they were students together. Their daughter, Kate, would spend whole Saturdays in her father’s studio but it wasn’t until she was 11 or so that she began to understand her parents were part of art history. “One of my classmates in grade school had one of the prints that my mom modelled for,” Kate smiles. “She was like, ‘Your mom’s hanging naked over my couch!’ I didn’t know what to say about that!”

Like Serra, Kate believes his work has been unfairly misconstrued as sexist.

“It was so completely the opposite of who he was and how he treated women in real life. He had the same wife for so many years and as their daughter I watched them be madly in love until he died. It was kind of disgusting,” – she laughs – “everybody was like, how do they have this wonderful, perfect marriage? I mean, he’s my dad so I don’t want to entirely think about it, but finding my mom he was reawakened by sex, so I think that really was a driving force – this woman he loved and was completely attracted to.”

Wesselmann is the only one of the great American pop artists never to have been feted with a New York retrospective, an oversight he hoped would be corrected posthumously. “He actually wrote two different speeches to be read at his retrospective,” Kate says. “I don’t know how serious they are!.”

His commitment, however, was utterly serious. Wesselmann painted up until the very end (his Sunset Nudes are now some of his best-loved works), even when he was so frail he needed Claire to escort him from his apartment to the nearby studio. “He said to me that every brushstroke was physically painful, but he couldn’t stop,” she says.

At the very end, she says, it was those collages – his beginning – that he returned to. He ran out of time, but one of his planned paintings was a large-scale reworking of 1960’s Judy Trimming Toenails, a warm-toned, simple and stately composition of a woman in a wide brimmed hat, holding her left foot in her hands.

His daughter smiles: “I would have liked to see that made.”

• Tom Wesselmann: Collages 1959-1964 is at David Zwirner gallery, London from 26 January to 24 March