VIENNA — Toward the end of his life, the Austrian designer Josef Frank made dozens of meticulously detailed paintings of houses. Each was in a recognizably Modernist style, usually in a rural setting, with an elegant garden and large windows carefully positioned to capture the daylight.

Frank, who died in 1967 at the age of 82, was then living in Sweden, where he was renowned as a furniture and textile designer, but he had failed to replicate his success as a young architect in Austria after fleeing the country in the 1930s fearing Nazi persecution.

The houses in the paintings were ones that he longed to build. Frank gave some of the pictures to friends, hoping that they might commission him, but none did.

Eighteen of those paintings are now on display here at the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts/Contemporary Art, or MAK, in “Josef Frank: Against Design,” the biggest exhibition of his work in more than 30 years. The show, which runs through April 3, aims to establish Frank as “the great humanist in modern architecture and design,” according to Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, the museum’s director.

The co-curators of the show, Sebastian Hackenschmidt and Hermann Czech, an Austrian architect, have amassed several hundred examples of Frank’s work. Starting in his student years, the exhibits include furniture, architectural plans and models, textiles, drawings, those forlorn paintings of unbuilt houses, and three staircases (one of his obsessions) which until now had never been built.

“Frank is one of the most underrated architects and designers of the 20th century,” Mr. Hackenschmidt said. “His work is impossible to categorize, as he refused to align with any of the design movements of the time, or to develop an identifiable style.”

That may have been to Frank’s detriment. His output was bafflingly eclectic, from Cubist-influenced houses to reinventions of Shaker chests and 18th-century English wooden chairs. Determined to use design as a means of enriching daily life, Frank created objects to last and focused on then-unfashionable qualities like comfort and ease in the hope that people would feel relaxed with his designs.

Unlike many of his peers, he relished the prospect of clients changing things around to suit their needs. “The house is not a work of art, simply a place where one lives,” he wrote.

“Other Austrian architects of the day, Josef Hoffmann especially, believed in the interior as a ‘Gesamtkunstwerk,’ or complete work of art to be preserved intact,” Mr. Hackenschmidt said. “Frank was absolutely against that, and also against the standardization of Modernism, and Le Corbusier’s idea of buildings being designed as machines.”

Frank was born in 1885 near Vienna, where he studied architecture. He flung himself into the city’s dynamic design scene in the 1910s and 1920s, becoming a founding member of the Vienna Werkbund, a group of progressive designers.

His love of congeniality and spontaneity was apparent in his first design project, the 1910 interior of the apartment of his sister Hedwig and her new husband, Karl Tedesko. Antique furniture and carpets were combined with Frank’s own designs, inspired by such disparate influences as the Italian Renaissance, folklore, neo-Classicism, Biedermeier and Viennese Modernism. He emblazoned the couple’s initials and the year of their marriage on the doors of a series of marquetry cabinets, each of which was light enough to be moved easily.

The exhibition shows how Frank reinterpreted a similarly eclectic mix of historic influences in the chairs, tables and cabinets he designed for Haus & Garten, a company he co-founded in 1925, and his houses for wealthy Viennese clients. The exteriors of the houses were executed in a conventionally elegant Modernist style, but Frank was more concerned with making the experience of living there as pleasant as possible, for example by carefully studying the natural light in each room and adding smallish spaces with no obvious functions that occupants were free to use as they wished.

His work was not limited to the wealthy. Austria suffered from a severe housing shortage after World War I, and Frank emerged as a leader of a group of design activists who campaigned for affordable homes to be built. The workers’ apartments he designed had attractive views, good airflow and abundant light.

By the early 1930s, he had sealed his reputation as an influential architect, interior designer and design reformer, but in 1933 with Nazism on the rise, Frank, who was Jewish, made the decision to leave Austria with his Swedish wife, Anna, to live in her homeland. For the next few years, he designed Swedish holiday homes and furniture for a Stockholm company, Svenskt Tenn, while returning regularly to Vienna. But after Haus & Garten was forced to close in 1938, Frank never worked in Austria again.

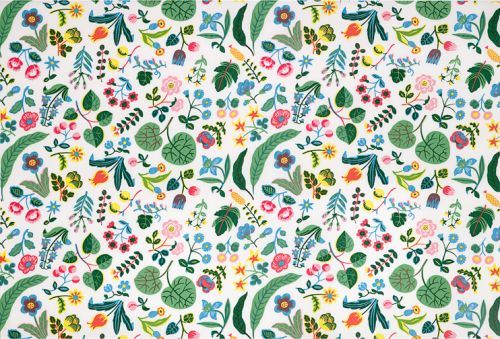

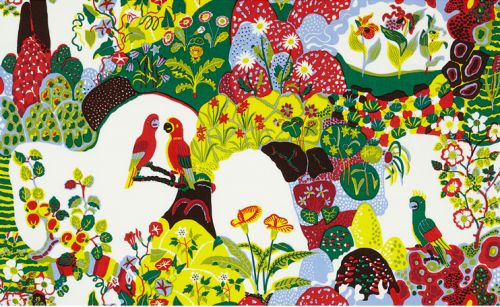

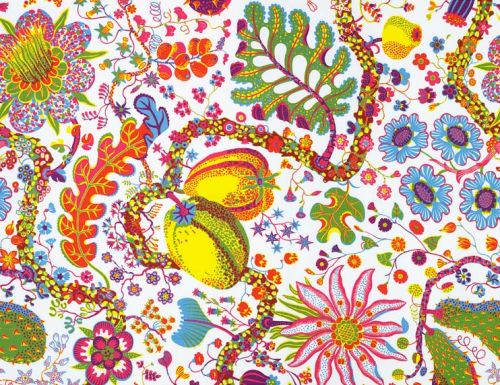

He and Anna left Sweden for the United States during World War II. Frank taught at the New School in New York and tried unsuccessfully to work on public housing projects. After their return to Sweden in 1946, he abandoned architecture (except in his paintings), and focused on Svenskt Tenn. There, he reinterpreted favorite historic styles again in more than 2,000 pieces of furniture, but he was — and remains — best known for the textiles he designed featuring surreal organic forms in vibrant colors.

Seductive though those textiles are, the MAK exhibition makes a case for the importance of Frank’s architecture, not least by showing how elements of his work that were considered odd by his contemporaries, like nostalgia and improvisation, have been embraced by successive generations of architects, including Denise Scott Brown and Rem Koolhaas. His commitment to affordable housing is especially timely given its popularity among young design activists, like the architects in Assemble, a British group that recently won the prestigious Turner Prize for its community projects.

“Frank was interested in livability, and the idea of a humanistic architecture that grew with its inhabitants,” said Ilse Crawford, a British interior designer who has long admired him. “His thinking on design was insightful, human-centered and extremely relevant for our times.”

Yet Frank regarded his career as a disappointment. “It is not what I had imagined and what I wanted and would have been able to do, but rather only what I was able to accomplish under the circumstances,” he wrote in a 1948 letter to a friend. “When I look back it makes me very sad.”