The man who championed Damien Hirst is now seeking new talent to revitalise the ICA

First came the “modernists”: Van Gogh, Matisse and Picasso, with their disruptive take on traditional European art – a century of revolutionary painting and sculpture followed.

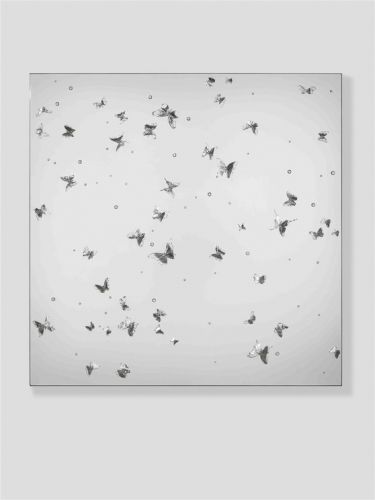

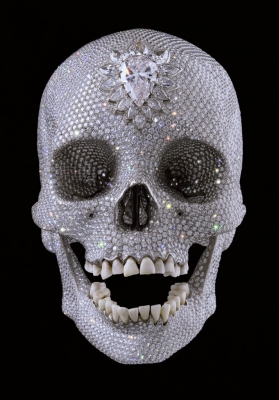

In the 1960s, “conceptual art” held sway, from Gilbert and George’s mischievous work to Yoko Ono’s symbolic “happenings”. Some of this glory was shared with irreverent pop art and stylish op art, but by the 1990s a fresh band of young British artists – including Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, Jake and Dinos Chapman and Sarah Lucas – were busy commenting ironically on sex, fashion, art and money until their own work became so valuable the joke was rather lost.

Now Britain badly needed a new avant-garde art movement to go beyond familiar shock tactics, said Gregor Muir, former champion of the YBAs and director of the renowned Institute of Contemporary Arts, in a passionate plea for unknown artists to be allowed to create a true subculture away from the art market of the ultra-rich and celebrity retrospectives.

“If we are looking for something radical, it is not always about shocking people. It is about being more pernicious, about getting under people’s skin,” said Muir. “Finding a real sub-culture is more important now than just calling something the new ‘avant-garde’. We need to hear a voice from cultures that are not represented well elsewhere.”Advertisement

Muir, who took over the ICA five years ago as it faced financial ruin, is celebrating the London venue’s 70th birthday this month with a bold plan to ensure artists have somewhere non-commercial to think. He believes creative talent should be able to develop ideas without immediately appealing to exclusive dealers and wealthy collectors.

“You don’t find that place inside a successful gallery and you don’t find it in a museum, either. In the ICA, an artist can work ideas through. This institute was founded by artists and enthusiasts as a place to go and make things,” said Muir. “The reason for our existence has become more important. What happens to art if you lose that middle ground? What happens to the artist who is not yet a commercial proposition or who makes something with no obvious sales element?”

Muir came to the ICA after working at Tate Modern and with leading independent gallery Hauser and Wirth. He is also the author of Lucky Kunst, a popular 2009 account his of the time he spent with the emerging stars of the YBA movement in the 1990s. This month, the ICA was given £187,495 by Arts Council England and has been encouraged to apply for a grant of £1.2m to improve Nash House, its home on the Mall since 1968.

Muir said London had never been so tough for artists with difficult things to say: “A commercial gallery understandably has an agenda and promotes its interests. But many are so big and powerful that they also mimic what a museum can do, rather than being experimental.”

His words underlined the fears of Andrea Phillips, a former lecturer at Goldsmiths College who works at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. In a recent study, she claimed this generation of art students faced “no future of any sort”. There were no affordable places to work or make the connections needed to “sweet-talk the rich elite into sponsoring them”.

“These people see inequality clearly at the biennial, at the art fair, at the museum dinner (to which they are not invited). They are mainly speechless. Their dispossession is done in the name of art’s general value,” she said.

Sir Roland Penrose, co-founder of the ICA, once said its role was “stimulating interest in the works of artists and ideas formerly unfamiliar to us”. However, after a troubled time in 2002, critics felt it was failing and its controversial chairman, Ivan Massow, was sacked after describing most contemporary art as “pretentious, self-indulgent craftless tat that I wouldn’t accept even as a gift”.

In 2010, after receiving emergency funds and an ultimatum from the Arts Council, ICA director Ekow Eshun and chairman Alan Yentob resigned and Karsten Schubert, the art dealer and writer, said it had been left behind by its London rivals: “The pivotal role the ICA once played was possible because it was really the only venue for cutting-edge art. If the venue has lost that status now, it is because the cutting-edge has become so ubiquitous.”

In planning a stable future for the ICA, Muir hopes to hold on to its club-like atmosphere and refurbish Nash House. Exhibitions this year include the first solo celebration of punk jeweller Judy Blame and the album designs of punk band Public Image Limited.Its programme of film and live performance will also continue.

“It has never been an easy place to maintain – there have always been ups and downs,” said Muir, adding that his job was to continue the debate about what an avant-garde should be. “There is no other major venue prepared to lend its weight to territory so far away from the established view.”

http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2016/jan/24/british-artists-new-avant-garde-ica-damien-hirst